You are here

Quo Vadis Kosovo? High time to realign with the West

Introduction

The ongoing war in Ukraine has significantly altered the geopolitical landscape, further elevating tensions in the Western Balkans. Russia’s increased meddling has worsened the region’s security situation. Western countries have repeatedly warned about various tools that Russia employs to destabilise the region, aiming to distract the West from providing financial and military aid to Ukraine. Meanwhile, tensions between Kosovo* and Serbia are rising, secessionist threats persist in Bosnia and Herzegovina, while electoral victories by right-wing nationalist forces in North Macedonia have already sparked friction with the EU and its Member States. As NATO boosts its military presence in Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina, the EU and the United States are facing pivotal elections, against a backdrop of multiple global crises.

Following unrest in the north of Kosovo (1), where ethnic Serbs make up the majority of the population, in May 2023 the EU imposed temporary measures, including the suspension of high-level visits, contacts and events, as well as restrictions on financial cooperation. In September 2023, an armed group linked to Belgrade entered the village of Banjska, where in a shootout with the local police, classified by the EU as a terrorist attack, one police officer and several gunmen were killed. Western frustration with Kosovo further intensified in January 2024 after the Central Bank of Kosovo decided that the euro was the only legal currency, effectively banning bank transfers from Serbia to Kosovo Serbs and other minority communities, who receive salaries and pensions in dinar. Despite seven rounds of negotiations, the EU has indicated that parties have not been able to find a compromise solution to the issue. Kosovo’s membership of the Council of Europe (CoE) was postponed on 17 May 2024, due to Pristina’s refusal to implement commitments made as part of the agreements reached within the EU-facilitated Dialogue between Belgrade and Pristina. This has reinforced Western concerns that the government in Pristina is continuing to obstruct the Dialogue process, alongside Belgrade. In this climate of defiance, any unilateral actions taken by Belgrade and/or Pristina risk a dangerous escalation, potentially plunging the region into another vicious spiral of violence. This Brief contends that there the current adverse geopolitical conditions significantly increase the potential for political instability and insecurity in Kosovo, and outlines strategic steps to avert further escalation between Kosovo and Serbia.

*This designation is without prejudice to positions on status, and is in line with UNSCR 1244 (1999) and the ICJ Opinion on the Kosovo declaration of independence.

The path of diplomacy

The HR/VP, Josep Borell, has more than once described the talks between Kosovo and Serbia as ‘crisis management’, underlining the precariousness of the situation (2). The landmark Agreement on the Path to Normalisation of Relations between Kosovo and Serbia (also known as the Ohrid Agreement) and its Implementation Annex (3), reached in February and March 2023 respectively, did not produce the expected results, due to disagreements on the sequencing of implementation steps. This Agreement is inspired by the 1972 German-German Basic Agreement and stipulates, among other points, that Kosovo pledges to ‘ensure an appropriate level of self-management for the Serb community’, including through the establishment of an Association of Serb-majority Municipalities (ASM) – a commitment from 2013 – while Serbia does not object to Kosovo’s membership in international organisations. Almost none of the commitments have been implemented, while new issues, with a potential to further destabilise the situation, pile up.

Kosovo is stuck. Its aspirations to join the EU and NATO are stalled.

Kosovo is stuck. Its aspirations to join the EU and NATO are stalled. Another major obstacle on the path to EU accession is the continued non-recognition by five EU Member States. While Spain’s recent recognition of Kosovo passports and granting of visa-free travel to the country is a step in the right direction, Brussels has yet to formally review Pristina’s EU application. Similarly, promises of a clear path to NATO’s Partnership for Peace (PfP) programme are on hold. EU financial assistance, including substantial funds from the new Reform and Growth Facility, has been frozen.

Data: EUISS research based on open online sources; European Commission, GISCO, 2024; Natural Earth, 2024

Kosovo misjudged the West’s response following the outbreak of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. The new leadership resorted to unilateral actions in the Serb-majority municipalities in the north, triggering a security escalation between July 2022 and May 2023, following which NATO-led KFOR troops were forced to intervene as peacekeepers. These actions, encouraged by Belgrade, led to the mass resignation of local Serbs from the police, the judiciary and municipal institutions. Western frustration with the central government’s unilateral escalatory actions in northern Kosovo resulted in the imposition of ‘measures’ against Pristina. The EU outlined three conditions for lifting these measures, noting that it expected Kosovo ‘to act in a non-escalatory way’, that ‘early elections should be announced as soon as possible in all four municipalities’, and that it expected ‘Kosovo Serbs to take part in these elections’ (4). A process was initiated for a referendum aimed at the removal of ethnic Albanian mayors, which took place on 21 April and was boycotted by local Serbs backed by Belgrade. The Serbs in the north are also boycotting the census that is currently being conducted in Kosovo, although the legislation anticipates imposing heavy fines on individuals who refuse to participate in the census.

Walking a security tightrope

Kosovo has in place a three-tier security mechanism, according to which the Kosovo Police (KP) is the first security responder, the EU Rule of Law Mission (EULEX) the second and KFOR the third. This setup grants the KP the authority to operate over the entire territory of Kosovo. In November 2022 the Police Directorate in the north refused to implement the decision to replace vehicle licence plates issued by Serbia with Kosovo-issued ones. This triggered a wave of resignations among Serb officials, including in the Serbian-backed police force. The integration of Serb police officers into the Kosovo security apparatus was one of the key successes of the 2013 Brussels Agreement as it ensured the peaceful reintegration of both communities into the joint structure of the KP.

A major obstacle on the path to EU accession is the continued non- recognition by five EU Member States.

Today, the KP faces a twofold challenge: the first concerns efforts by Serbs to undermine police authority from within and the second concerns growing distrust among the local Serb population who remain suspicious of the increased presence of special police forces in the north. Moreover, public opinion in Kosovo regarding compromises on national identity issues, including the establishment of the ASM, has hardened considerably. In the 2021-2023 period, the number of citizens unwilling to make any compromise on these issues almost doubled, from 48% in 2021 to 80 % in 2023 (5).

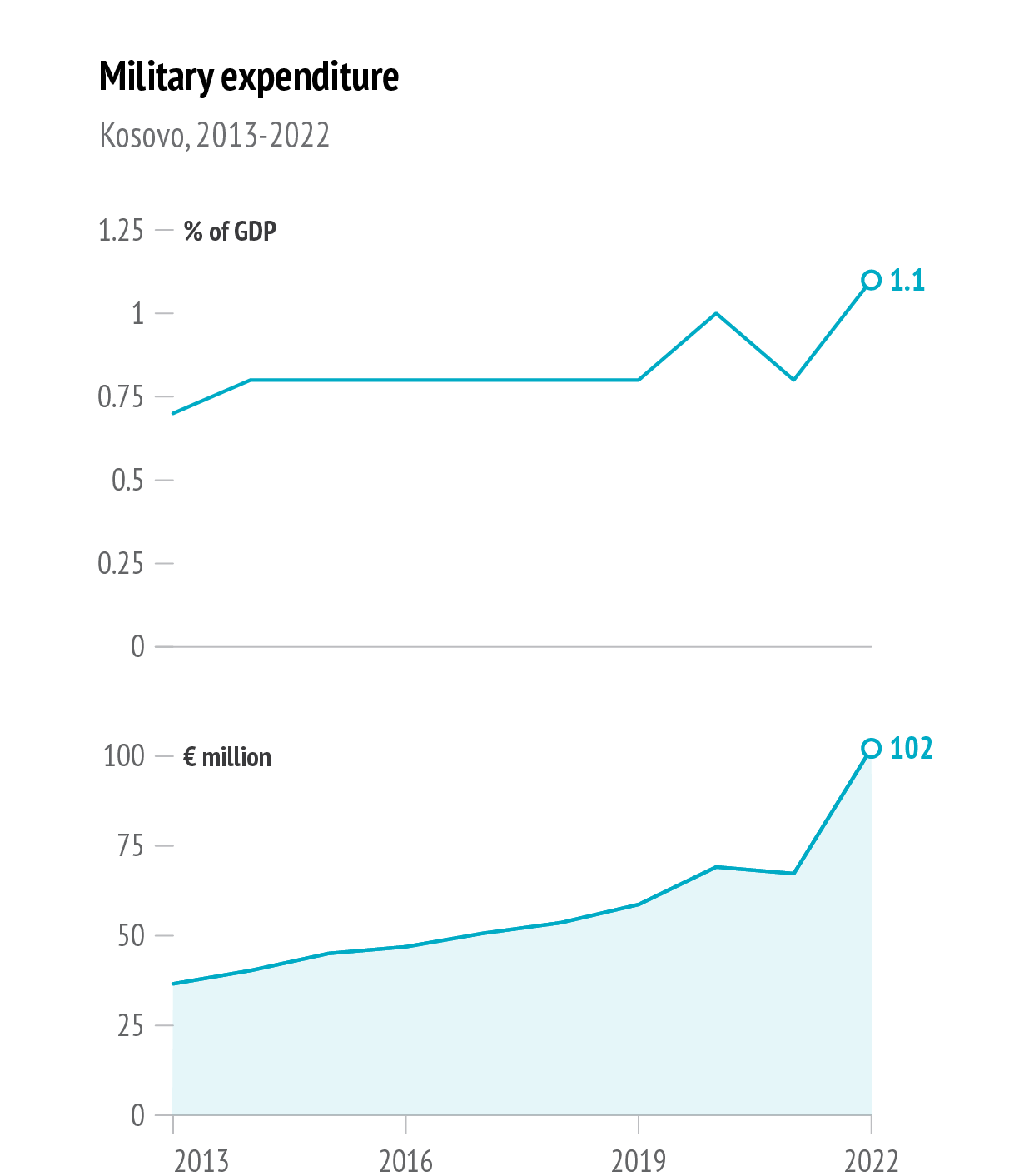

The 2022-2027 Kosovo Security Strategy identifies ‘Serbia’s territorial claims, violation of sovereignty by illegal structures [...] and ongoing efforts of the Serbian state to prevent Kosovo’s advancement and integration into Euro-Atlantic structures and other international organizations’ as the core security threat. Kosovo’s military expenditure has risen in recent years, increasing from 0.7% to 1.1 % of GDP between 2013 and 2022 (see graph opposite). The defence and security budget further increased by 22 % in 2024 compared to 2023 and is projected to reach €370 million this year (6). This needs to be seen within the regional context, where other countries have also been steadily increasing military spending. Notably, Serbia is the only one to have surpassed the 2 % GDP spending threshold: its budget has grown significantly, from €725 million in 2018 to €1 371 million in 2023 (7).

The increase in military expenditure coincides with the plan to transform the Kosovo Security Force (KSF) into an army by 2028. In 2021, the US donated 55 armoured security vehicles, while in January 2024, the State Department announced the delivery of 246 Javelin FGM-148F missiles, along with tracking equipment valued at €69 million (8). Under the 2021 contract, Türkiye provides a €9.7 million annual military equipment allowance. In 2023, Türkiye sold a batch of Bayraktar drones to Kosovo. The UK and Germany also closely collaborate with the KSF, providing training, equipment and military assistance in full compliance with NATO standards.

Data: World Bank, 2024; European Central Bank, 2024

The KSF’s operational scope remains limited; without KFOR’s consent the KSF cannot engage in missions in the north. This underscores the continued necessity of KFOR’s international presence and EULEX’s role in establishing long-term peace and stability. While the ultimate goal should be the full autonomy and accountability of the KSF as Kosovo pursues international recognition, in the interim, the focus of international actors should be on deterring conflict escalation and facilitating a peaceful transition during the post-conflict period.

Facing a new reality

With global elections looming and the war in Ukraine casting a long shadow, stabilising the security situation in Kosovo and the Western Balkans is crucial. As the region faces serious security and political challenges during this transitional period, it is essential to keep a vigilant eye on potential flashpoints, particularly in the north of Kosovo.

In the short run, sustained Western diplomatic engagement with both Belgrade and Pristina throughout the second half of 2024 is crucial. Otherwise, the risk of renewed security escalation is high.

The Kosovo government needs to urgently adopt and enact a positive agenda for the local Serbs, including steps to finally establish the ASM and to restore trust by addressing their legitimate concerns. Following the failure of the referendum to remove mayors in the north, Kosovo should reinitiate the dialogue with the EU on the conditions for removal of the imposed measures.

In the long run, several recommendations emerge:

Diplomatic engagement: The EU should intensify diplomatic efforts with the 5 EU Member States who have declined to recognise Kosovo’s independence, especially because the EU 27 Member States have jointly sponsored the ‘Ohrid Agreement’ which calls for Kosovo’s membership in international organisations. Upon fully aligning its position with the QUINT countries (9), Kosovo should collaborate with them to initiate a dialogue with the five EU non-recognising states on EU and NATO membership. Kosovo should also push for the opening of reciprocal liaison offices in capitals where such a presence is currently lacking.

Building bridges: Kosovo has much to lose if it persists in rejecting the EU’s recommendations and requests. It stands to greatly benefit by making an effort to improve relations with the local Serbs and exploring new avenues for facilitating the election of new mayors and municipal councillors in its northern municipalities, honouring its commitments and re-engaging in good faith in the EU-facilitated Dialogue. Finally, removing Kosovo’s veto on regional agreements would remove a key obstacle to enhanced Western Balkans regional cooperation and help foster socio-economic collaboration within the region.

EU conditionality, red lines and membership: As soon as the new College of Commissioners is in place, the EU should adopt a robust political strategy to incentivise continued collaboration between Kosovo and Serbia. There is no other viable alternative to the Dialogue. This could involve implementing stricter conditionality on the adherence to Brussels/Ohrid provisions by both parties, and clearly delineating red lines that cannot be crossed, including a clear timeframe for EU membership for both countries.

Security preparedness and deterrence: NATO can further support Kosovo’s security structures by developing their capabilities to effectively respond to emergency situations. This could include increased training exercises and joint operational planning, as well as strengthening the KSF’s defence capacities, particularly in response to security challenges in the north, such as the Banjska attack. In the long run, this will serve to further enhance the interoperability of the KSF with NATO standards, potentially paving the way for Kosovo’s eventual inclusion in the PfP framework.

References

1. Kosovo held municipal elections in four northern Serb majority municipalities, boycotted by the Serbs, with only 3 % participation of Kosovar Albanians. The new mayors took office accompanied by special police forces, resulting in protests by the local population, and injuries to almost 100 KFOR soldiers.

2. European External Action Service, ‘Kosovo-Serbia: Press Remarks by High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borell after the crisis management meetings with Prime Minister Kurti and President Vučić’, June 2023 (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/kosovo-serbia-press- remarks-high-representativevice-president-josep-borrell-after-crisis- management_en).

3. For more on this see (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/belgrade- pristina-dialogue-agreement-path-normalisation-between- kosovo-and-serbia_en) and (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/belgrade-pristina-dialogue-implementation-annex-agreement-path- normalisation-relations-between_en)

4. European Council of the EU, ‘Kosovo*–Statement by the High Representative on behalf of the EU on the latest developments’, 3 June 2023 (https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/06/03/statement-by-the-high-representative-on-behalf- of-the-eu-on-kosovo-and-latest-developments/).

5. Republican Institute Survey, ‘National Survey of Kosovo February-March 2023’, Center for Insights in Survey Research (https://www.iri.org/wp- content/uploads/2023/05/Kosovo_2023_public_poll.pdf).

6. Prime Minister’s Office, ‘The complete speech of Prime Minister of the Republic of Kosovo, Albin Kurti’, 16 November 2023 (https://kryeministri. rks-gov.net/en/blog/the-complete-speech-of-the-prime-minister-of-the-republic-of-kosovo-albin-kurti-at-the-plenary-session-of- the-assembly-in-the-first-review-of-the-draft-law-on-budget- allocations-for-the-year-2024/).

7. Belgrade Centre for Security Policy, ‘Balkan Defence Monitor’, 2023 (https://bezbednost.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Balkan-Defence- Monitor-2023.pdf).

8. Anđelka Ćup & Euronews Serbia, ‘Kosovo to receive weapons from the US as part of military development plan’, 17 January 2024 (https://www. euronews.com/2024/01/17/kosovo-to-receive-weapons-from-the-us- as-part-of-military-development-plan).

9. The Quint is an informal decision-making group consisting of France, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and the United States.