You are here

Rehearsing for war: China and Russia's military exercises

Introduction

China and Russia have a shared interest in revising the global political order, which they perceive as overly dominated by the United States and its allies. Their current rapprochement is primarily driven by this concern, and facilitated by the absence of a perceived mutual threat between the two countries (1).

Military cooperation is a cornerstone of the Sino-Russian partnership. This cooperation, which has fluctuated at various points in the past (2), has rapidly consolidated over the past decade (3). It has entailed a limited number of mutual transfers of technology including, much to the concern of the EU, exports from China of dual-use technologies which indirectly support Moscow’s war against Ukraine (4). This Brief looks at yet another important aspect of Sino-Russian military cooperation – combined military exercises, often including air and naval patrols.

These exercises matter for three reasons. They signal to adversaries and partners alike the combined ability to defend, deter and project power at distance, and can also serve to express disapproval of actions or political initiatives undertaken by other parties. In this sense, the exercises serve as calculated displays of military power, functioning as a form of strategic communication. But they can also be more broadly revealing of capacities and intentions. Finally, these exercises provide crucial operational experience, particularly for Beijing, which has not engaged in a real war during the last 45 years.

More frequent and complex

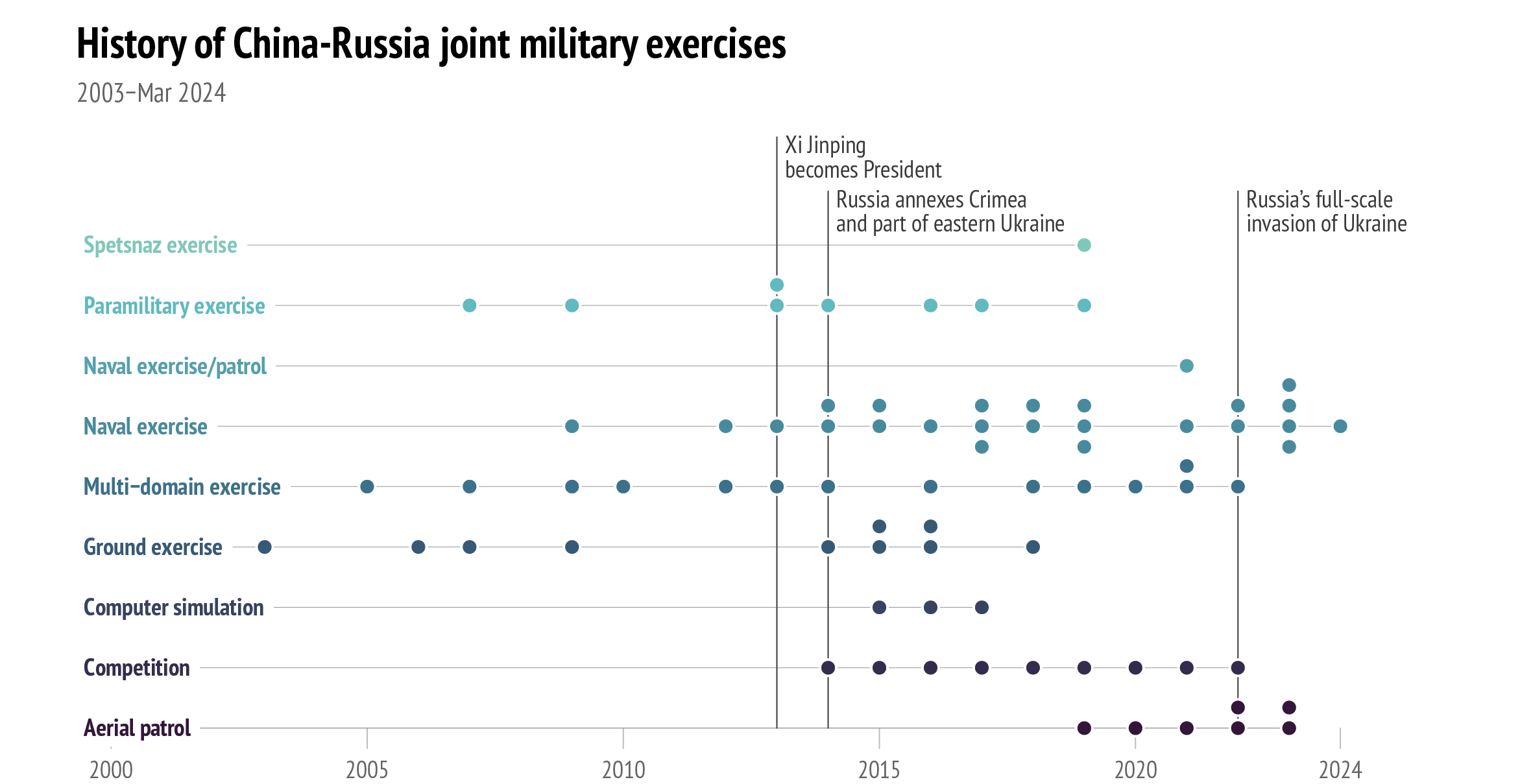

Our analysis covers 66 military exercises conducted since 2003 when Russia and China first participated in a combined exercise under the aegis of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). It encompasses both bilateral and multilateral exercises, conducted either on land, air and sea or in multiple domains, as well as computer simulations (CPX).

Data: EUISS research based on various Chinese and Taiwanese new outlets; Taiwan Institute for National Defense and Security Research, 2024

The data shows a steady yet nonlinear increase in the frequency of joint exercises. The 2000s witnessed minimal activity, followed by a rise after the annexation of Crimea in 2014 when an unprecedented 5 joint exercises were conducted, while their number rose to 7 two years later. The Covid pandemic and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine (2022) caused a temporary plateau, not due to a lack of interest but more likely due to resource constraints. Recently there has been a renewed increase, with a record number of combined patrols and exercises (4) being carried out in 2023. While Russia will continue to struggle to commit resources to more extensive activities, including annual strategic command staff exercises in which China has participated (5), the rising frequency suggests China’s continued interest in conducting such exercises and their perceived importance at a time when the United States and its various Asian allies are stepping up their defence cooperation.

The complexity of joint exercises has also been increasing in parallel to their frequency. Earlier manoeuvres and deconfliction exercises have evolved towards more jointness, including establishment of joint command centres or air force landings at each other’s airports. They now also feature more coordination, with troops training to use each other’s more high-end military equipment. Finally, they are based on more complex scenarios, having evolved from counterterrorism drills to simulated joint operations in regional wars. Multidomain exercises, first introduced early in the framework of the SCO to counter against the ‘three evil forces’ of terrorism, separatism and extremism, have become more common compared to earlier more compartmentalised land drills. However in recent years resource constraints in Russia have led to an increase in single domain (sea or air) exercises, although joint exercises remain more prevalent overall. This trend is likely to continue despite the 70 % increase in the defence budget (projected to be 29 % of total state expenditure and around 7.1 % GDP in 2024) (6) as these resources will be channeled towards the war effort or reducing the defence industry’s accumulated debts.

Despite significant progress, the Sino-Russian militaries remain much less interoperable than NATO’s forces. Combined exercises currently focus on the ability to operate side-by-side in military theatres. However, the increasing complexity of these exercises warrants attention. Not only does it indicate growing mutual trust; it also suggests a shift towards deeper coordination, which could pave the way for future joint operations in pursuit of shared interests.

Strategically located

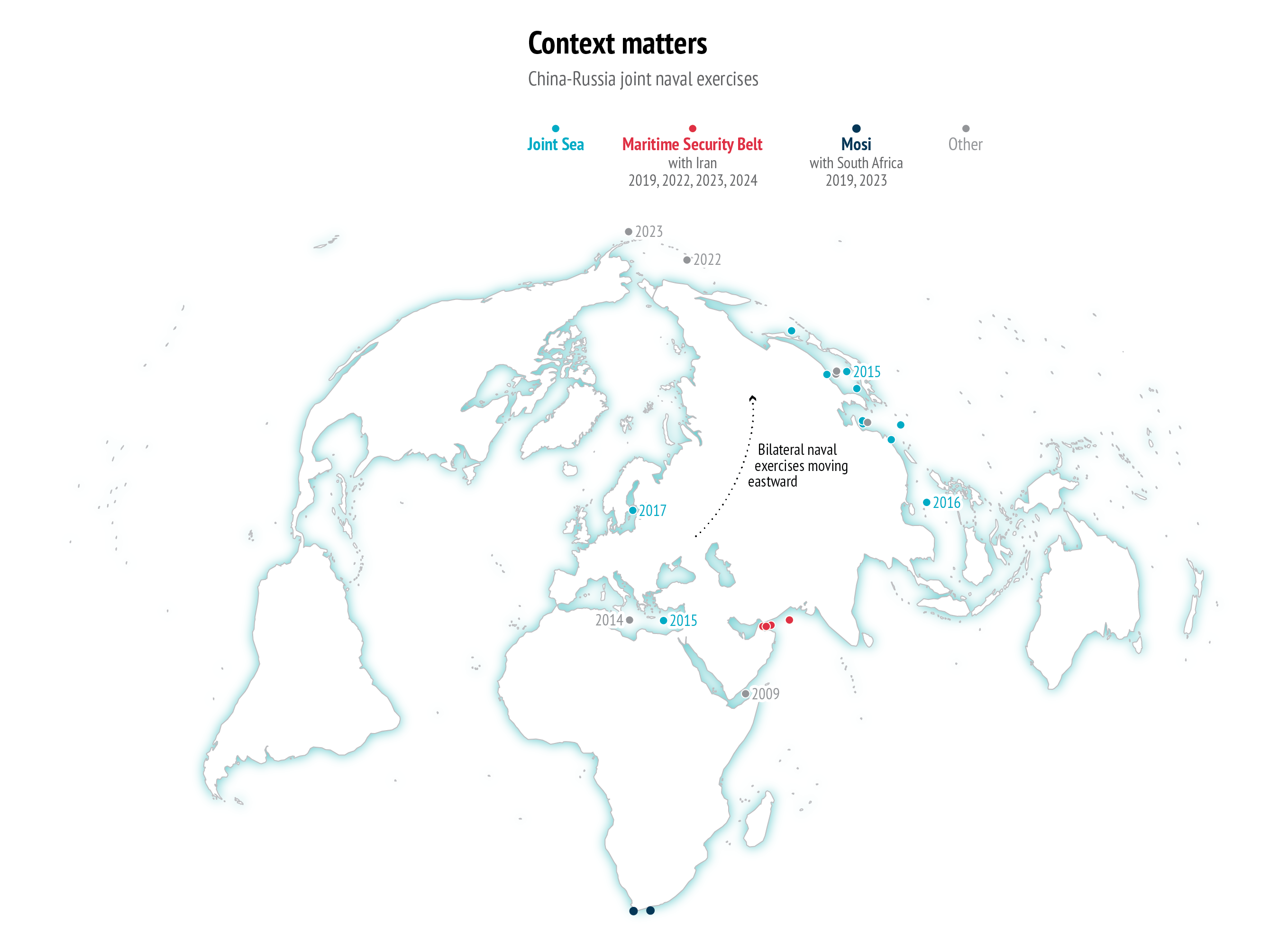

The rise in the frequency of exercises goes hand-in-hand with an increase in the number of exercises conducted further away, often in contested areas and/or close to adversaries’ territorial waters, reflecting the growing prominence of naval drills, which now account for 35 % of all joint exercises to date. The first joint naval exercise, held in the Gulf of Aden in 2009, was held in a distant region crucial for global maritime trade but that was not contested or close to territories controlled by rival powers at the time. The immediate context was the international effort to battle piracy in the region. But since 2012 combined naval exercises spanning the Mediterranean Sea, Black Sea, Gulf of Oman, East China Sea, South China Sea, the Baltic Sea, Sea of Japan, South Atlantic, and the Pacific Ocean have often taken place in or in proximity to disputed areas or competitors’ waters.

The most recent of the exercises off the coast of Alaska, Northern/Interaction (2023), was particularly significant in this respect, both in terms of geographical scale and proximity to US territory. The combined Chinese and Russian fleet, comprised of 11 vessels, sailed from the Sea of Japan to the Chukchi and Bering Seas – entry/ exit points for the Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route that traverse the increasingly contested Arctic – and passing close to the Aleutian Islands. The declared aim of the exercise was ‘safeguarding the safety of strategic maritime passage’ (7). According to Russia’s Ministry of Defence, the exercise involved communications training, helicopter take-offs and landings between each other’s ships, and an antisubmarine exercise (8).

Two key observations emerge from analysing the changing locations of Sino-Russian exercises. First, there has been a recent eastward shift, with more exercises taking place in Chinese seas (particularly the East China Sea), while fewer exercises have been conducted in European seas. This trend extends to aerial exercises and patrols, which were only introduced in 2019 and have become more frequent in recent years. These have been taking place exclusively in the greater Asia region (Sea of Japan, East China Sea, South China Sea and the Western Pacific Ocean). Second, the global reach of some exercises has been expanding significantly in parallel, either in the form of bilateral or trilateral/multilateral exercises.

Data: European Commission, GISCO, 2024

Trilateral exercises like Mosi (‘Smoke’) with South Africa in 2019 and 2023, or the Maritime Security Belt with Iran in 2019 and 2022-2024, as well as multilateral ones, including Russia’s strategic command exercises, serve a dual purpose. They showcase China’s and Russia’s capacity to project military power on a global scale, while also potentially signalling new avenues of cooperation for partner nations. An example is the first ever Maritime Security Belt exercise conducted together with Iran (2019) less than a year after the US withdrew from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). While Russia had once cooperated overall with the P5+1 in constraining the development of Iran’s nuclear programme, it now engages in an unprecedented level of military cooperation with Iran encompassing drones, missiles and air defence systems that help sustain its war of aggression against Ukraine.

Locating exercises close to adversaries (Alaska, Honshu), in areas of rising geopolitical competition (Mediterranean, Black and Baltic Sea regions, or close to the disputed maritime zone in the South China Sea) or at significant distance has also been a means of signalling readiness to challenge rivals wherever they are. At times, these exercises have been timed to coincide with key events taking place in other states. In April 2023, Russian and Chinese warships sailed close to the Japanese islands of Okinawa and Miyako on the eve of the trilateral summit between the US, Japan and South Korea, obviously to signal their opposition to that summit. In a similar vein, in May 2024, China conducted military drills in the South China Sea on exactly the same day as a meeting between defence ministers from the US, Philippines, Japan and Australia.

Analysing exercises conducted in contested areas can offer insights into potential future conflicts envisioned by Russia and China – with the caveat that there is a deterrence dimension to these exercises. They are conceived to be read not as simple projections of the possible future for which the parties are preparing but also as ways of shaping this future by influencing adversaries’ behaviour. The Bering Sea Northern Interaction exercise (2023) is one example. Another is the Zapad/Interaction (2021) held in Western China, which marked the first time that the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) took the lead role. Here, the scenario involved joint attack, destruction of enemy forces (including in-depth defences by artillery strikes), followed by pursuit and annihilation of hostile forces. The exercise also featured paratroopers and special forces deployed to seize enemy defences, and the extensive use of drones (9). The immediate political context was the crisis in Eastern Ladakh in which China and India faced one another in a border standoff.

Conclusion: Expect more

The analysis of Sino-Russian military exercises, considering their frequency, complexity and scale, underscores the need for the EU to take these developments seriously. Military cooperation, particularly joint exercises, will continue to constitute an important aspect of the relationship between the two countries. The trend towards increasing complexity and the resolve to operate in more contested or distant theatres is likely to continue, while an uptick in less resource-intensive exercises cannot be ruled out.

The exercises reflect shared interests between Beijing and Moscow. Russia seeks to cultivate and showcase this partnership as China’s support is key to fuelling its war effort and avoiding diplomatic isolation. In its turn, China seeks to benefit by gaining operational experience for the rapidly modernising but as yet battle-inexperienced PLA, as well as the strategic advantage afforded by access to Russia’s air bases and Pacific Fleet facilities. However, as their relationship becomes overall more asymmetric in China’s favour, reflecting the latter’s growing power and capabilities, Beijing is likely to assume a progressively more prominent role in the exercises.

The eastward shift in exercise locations already reflects Beijing’s growing ability to promote its interests within this asymmetric partnership. However, the possibility of future joint Sino-Russian military exercises being relocated to European seas in the coming years cannot be ruled out. We may also see a diversification of trilateral exercises beyond China and Russia’s immediate neighbourhood, potentially involving a more ambitious global reach and new forms of interaction.

Their defence cooperation will not be formalised as a military alliance. China in particular has been averse to the concept of alliances and, as a matter of principle, refuses to sign alliance treaties with other countries. However, this does not preclude further upgrades in their cooperation. Recent military and diplomatic contacts indicate that there is strong willingness to continue to step up defence cooperation in the coming years – even at the cost of potentially diminishing returns for Moscow.

The EU must develop a comprehensive and realistic understanding of the shifting nature of Sino-Russian military cooperation. It should prioritise a thorough analysis of these exercises, focusing on their location, scenarios, partners in the tri-/multilateral drills, and any observed shifts in the participating countries’ roles. This analysis should consider not only their signalling function but also what they can reveal about Moscow and Beijing’s capacities, intentions and broader visions of future conflicts. By closely monitoring these exercises, the EU can gain valuable foresight regarding potential joint actions in contested regions with global implications, including in the Taiwan Strait. This analysis can also shed light on the evolving power dynamic within the Russia-China relationship overall.

References

* The authors would like to thank Lily Grumbach and Pelle Smits, EUISS trainees, for their invaluable research assistance, particularly for compiling the data for the visuals. The authors would further like to extend their thanks to participants at the EEAS (STRATPOL) briefing who provided valuable feedback on the preliminary research findings.

1. Based on this perception, Moscow moved troops from the 3,700 km-long border with China in the east towards the west following its invasion of Ukraine.

2. Hart, B. et al., ‘How deep are China-Russia military ties?’, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 9 November 2023 (https://chinapower.csis.org/china-russia-military-cooperation-arms-sales- exercises/).

3. Facon, I., ‘La coopération militaire et de sécurité sino-russe : des accents plus stratégiques,’ Annuaire français de relations internationales, 2024.

4. Rácz, A., ‘How Beijing is lending Moscow’s war effort a hand,’ Internationale Politik Quaterly, 5 September 2023 (https://ip-quarterly. com/en/how-beijing-lending-moscows-war-effort-hand); Snegovaya, M. et al., ‘Back in stock? The state of Russia’s defense industry after two years of war,’ Center for Strategic and International Studies, 22 April 2024 (https://www.csis.org/analysis/back-stock-state-russias-defense- industry-after-two-years-war).

5. China first participated in this exercise in 2018. However, in 2021 a separate China-Russia exercise, Zapad/Interaction, was held in China’s Ningxia region. While China did participate in the scaled-down Vostok exercise in 2022, Zapad (2023) was cancelled by Russia.

6. Cooper, J., ‘Another budget for a country at war: Military expenditure in Russia’s federal budget for 2024 and beyond,’ SIPRI, December 2023 (https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2023-12/ sipriinsights_2312_11_russian_milex_for_2024_0.pdf).

7. R. Adm. Qiu Wensheng, quoted by Liu Xuanzun, ‘China-Russia joint drills wrap up in Sea of Japan, to be followed by joint naval, air patrols in Pacific Ocean’, Global Times, 24 July 2023 (https://www.globaltimes.cn/ page/202307/1294976.shtml).

8. Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation, ‘Joint Russian-Chinese naval exercise “North/Interaction 2023” begins in Sea of Japan,’ 20 July 2023 (https://eng.mil.ru/en/structure/forces/navy/news/more. htm?id=12473390@egNews).

9. Raghavendra, R.M.V. Pavan, ‘Zapad/Interaction-2021: A new milestone in China-Russia joint military exercises,‘ Institute of Chinese Studies, 25 August 2021 (https://icsin.org/blogs/2021/08/25/zapad-interaction- 2021-a-new-milestone-in-china-russia-joint-military-exercises/).