You are here

Shifting tides: International engagement in the Horn of Africa and the Red Sea

Introduction

In the Horn of Africa (HoA) (1) and the Red Sea maritime and onshore security challenges are inextricably interlinked, prompting international concern. Initially, piracy arose from illegal fishing and the limited economic prospects for Somali fishermen. More recently, attacks by Yemeni Houthis on vessels in the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, which connects the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden, have further threatened key trade routes accounting for about 15 % of global maritime trade (2). In March 2024, damage to three of the 14 undersea cables in the Red Sea affected 25 % of data traffic between Asia and Europe (3). Houthis have attacked vessels more than 40 times since November 2023, while suspected pirate activity has also seen a rise, with 19 attacks carried out in 2024 compared to just 6 in 2023. Further complicating the situation, the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) recently signed between Ethiopia and Somaliland has generated mounting tensions with Somalia, with adverse repercussions for the fight against al-Shabaab as well as for internal conflict dynamics (4). Amidst a climate of mounting insecurity, a number of European, Asian and Gulf countries are deploying militaries, navies and diplomats. Meanwhile, notably China and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) are expanding trade relations and infrastructure projects in the region.

This Brief argues that it is vital for the EU to define its role in the increasingly complex political landscape emerging in the HoA and the Red Sea. It outlines three policy options for the EU to consider.

Guarding the horn

Most countries with interests in the HoA prioritise protecting vessels, international freedom of navigation, and safeguarding economic interests, including access to natural resources. However, predatory actors like the Houthis and pirates view disruptions in maritime routes as opportunities to expand influence, procure economic benefits and harm the economic interests of perceived competitors, such as Western powers. This has led to the increased presence of international maritime coalitions patrolling the waters around the HoA to counter piracy or drone attacks. Onshore military bases provide support to naval operations, including training for local armies or navies, and security for ports and trade routes. Djibouti hosts the highest number of military bases, with China, France, Japan, Italy and the United States having permanent bases, while Türkiye, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and the United Kingdom have bases in Somalia. Russia is seeking to build a base in Sudan (5). Naval operations in the area include three out of the five Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) task forces, with broad participation including the US, EU Member States and Gulf countries. The EU contributes with EUNAVFOR Atalanta and Aspides, respectively deployed against piracy and for vessel protection, while the US leads the multinational Operation Prosperity Guardian to ensure freedom of navigation (6). Thus, while maritime security commands a high degree of consensus among most international actors interested in the HoA, onshore security reveals deeper competitive undercurrents and underlying rivalries in the region.

Data: EUISS' own collection of data from multiple sources, 2024; ACLED, 2024; European Commission, GISCO, 2024

Competition for sea access involves not only regional actors like Ethiopia, but also countries such as the UAE, China and Türkiye which operate ports in the region. This competition intersects with both regional and international interests, as maritime routes offer strategic access to inland resources. It also intensifies existing regional rivalries, like the long-standing competition among Djibouti, Somalia, and Eritrea for dominance as Red Sea trade hubs. Local dynamics, such as the territorial and constitutional tensions between Somalia and Somaliland, further complicate the picture. The MoU between Ethiopia and Somaliland announced in January 2024 has heightened tensions, spurring international partners to seek a balanced approach that supports Somali territorial integrity without jeopardising partnerships with Ethiopia (7). Sea access reduces dependency and boosts trade for landlocked countries, while international partners also seek control of ports to ensure safer access to resources and markets. As a result, while onshore stability is crucial for overall economic investment and domestic security, particularly for Gulf countries and Egypt due to their geographical proximity, the pursuit of partnerships also fuels competition over access to ports, maritime routes and trade. The prevalence of conflicts in the region also creates opportunities for external actors to gain influence by backing warring parties during conflicts or periods of transition.

Partners, competitors and aspiring peacebrokers

The HoA is a hotbed of political rivalry, with states competing for influence in trade, security and development, and vying for coveted leadership roles in brokering peace deals. Expanding economic interests align with expanding political interests, shaping both regional partnerships and conflict resolution efforts. However, the proliferation of forums for addressing both development and security matters creates the risk of ‘forum shopping’ among warring parties, with a detrimental effect on peace prospects (8).

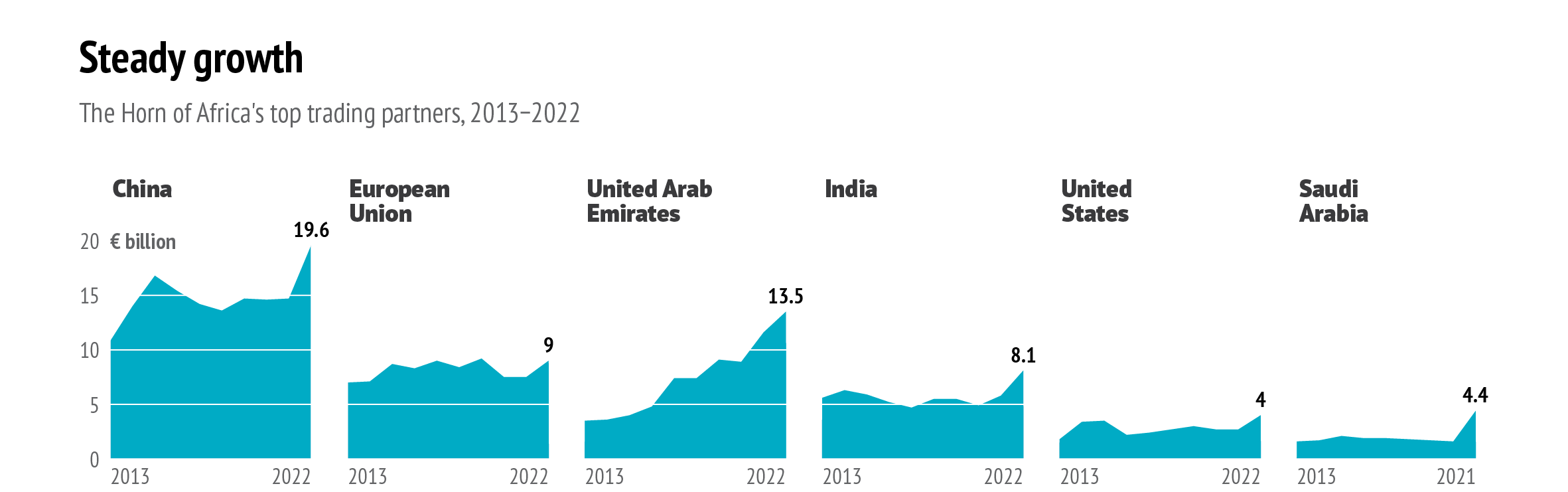

In 2022, China, the UAE, the EU and India were the region’s biggest trade partners, while between 2019 and 2022 Russia was the biggest supplier of military equipment to the region, followed by China and Belarus (9). However, regional conflicts have also become an arena for external actors to compete for leadership in brokering peace deals to increase their global influence. Examples include the 2018 Jeddah Peace Agreement between Ethiopia and Eritrea, the Pretoria Agreement for Ethiopia, international conferences for Somalia, Kenya’s emerging role in South Sudan, and various initiatives for Sudan, including the ongoing Jeddah process, the 2024 Paris humanitarian aid conference, and civil society consultations to foster inclusive dialogue (10). Regional initiatives, such as the Horn of Africa initiative, and the Council of Arab and African Coastal States of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, aim to address common development and security challenges (11).

The proliferation of forums for addressing both development and security matters create the risk of ‘forum shopping’ among warring parties.

In the security domain, the future of international support to Somalia in the fight against terrorism likely presents the next major test for regional security cooperation. As the African Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS) is scheduled to be wound down by the end of 2024, whether continued support to Somalia will develop multilaterally or bilaterally could be a test of the partners’ ability to prioritise cooperation over competition (12).

Deep-diving: Three options for the EU

In this increasingly complex situation in the HoA and the Red Sea, the EU needs first to invest in a deeper understanding of the broader Red Sea region, and then decide what role it wants to play. Three possible choices seem to emerge for the EU: damage control, competition for influence or a quest for cooperation.

In a damage-control scenario, the EU would mostly pursue bilateral cooperation with countries in the region, provide general support to regional organisations, and engage in limited cooperation with middle powers mainly focused on maritime security. This would involve significant attention to humanitarian aid, continued competition for leadership in peace processes, and development aid. Existing security initiatives such as the deployment of four common security and defence policy (CSDP) missions would continue to complement efforts in capacity building (EUCAP Somalia, EUTM Somalia) and deterrence to protect freedom of navigation (Atalanta and Aspides). However, this approach is unlikely to yield any concrete peace prospects or deter threats in the region beyond limiting their impact on EU interests. This posture would de facto align with the preference for bilateral ties favoured by Russia, the UAE and Türkiye among others. However, this may lead to an increase in forum shopping by national and sub-national entities in the region and fuel competition among partners. This approach might maintain the EU’s foreign policy in the region on minimal life support, preserving existing ties and safeguarding economic interests. However, it could also lead to the EU becoming politically sidelined due to a perception of the bloc having other priorities, for instance Ukraine, and an inconsistent position regarding conflicts worldwide. In this scenario, the EU will continue to play a role in maritime security, capacity-building, development and humanitarian support, but China and middle powers such as Gulf countries and Türkiye will gain greater influence.

Data: UN COMTRADE, Total Trade, 2024; European Central Bank, Annual exchange rates, 2024

In a competition scenario, the EU would take a tougher stance against rivals like Russia and China while leveraging its role as a development aid provider with stricter conditionality. This approach might lead countries in the region to align with either the EU or its perceived rivals, with a heightened level of risk. Due to its institutional rigidity the EU could struggle to adjust to rapidly evolving regional partnerships, hindering its ability to adapt. Increased competition among external actors in the region could exacerbate conflicts in Sudan, Ethiopia and Somalia, potentially jeopardising prospects for conflict resolution. Onshore competition may also weaken deterrence at sea, posing threats to freedom of navigation. This could create opportunities for various actors to exploit the situation and maximise their gains, for instance separatist regions seeking greater autonomy, or countries engaged in proxy conflicts like Iran. It could also negatively affect local dynamics by amplifying grievances that could increase the attractiveness of illegal activities, including piracy and terrorism.

In a cooperation scenario, the EU could achieve broader gains but would need to adjust its approach to projecting influence in the wider region. The EU’s influence would hinge on its capacity to build cooperation with middle powers like Türkiye and Gulf countries. This would imply bringing the HoA to the table when interacting with these countries and exploring potential for cooperation and more targeted actions. Diplomatic efforts in this direction could discourage forum shopping by countries and sub-national entities in the region, thus facilitating concerted efforts towards conflict resolution, and help to protect shared interests like freedom of navigation. Recognising that complete alignment on values may not be achievable, this diplomatic approach could foster cooperation when interests coincide, such as in combating piracy, terrorism and their root causes. Moreover, it could help promote a more prominent role for regional organisations weakened by internal competition and forum shopping. In fact, despite limitations in their conflict resolution capacity, the EU’s continued support for the African Union (AU) and IGAD remains vital to prevent their complete loss of legitimacy, which would severely hamper their effectiveness. Clearly, given the regional dimension of most challenges in the HoA, a well-coordinated approach between the AU and the relevant Regional Economic Communities (RECs) could be more effective than the purely bilateral approach advocated by many partners. Overall, in this cooperative scenario a heightened sense of urgency would likely incentivise external partners to join efforts and leverage influence to facilitate de-escalation, reduce forum shopping and explore negotiated solutions to the region’s ongoing conflicts.

References

*The author would like to thank Adam Eskang for his research assistance.

1. The HoA is here understood to comprise the member states of the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD).

2. IMF Blog. ’Red Sea atttacks disrupt global trade’, 7 March 2024 (https:// www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2024/03/07/Red-Sea-Attacks-Disrupt- Global-Trade).

3. BBC News, ‘Crucial Red Sea data cables cut, telecoms firm says’, 5 March 2024 (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-68478828); Stronge T., ‘What we know (and don’t) about multiple cable faults in the Red Sea’, TeleGeography, 5 March 2024 (https://blog.telegeography.com/ what-we-know-and-dont-about-multiple-cable-faults-in-the-red- sea).

4. BBC News, ‘Who are the Houthis and why are they attacking Red Sea ships?’, 15 March 2024 (https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle- east-67614911); EUNAVFOR Atalanta, Key facts and figures (https:// eunavfor.eu/key-facts-and-figures), International Crisis Group, ‘The stakes in the Ethiopia-Somaliland deal’, 6 March 2024 (https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/ethiopia-somaliland/stakes-ethiopia- somaliland-deal).

5. Caprile, A. and Pichon, E., ‘Russia in Africa: An atlas’, Briefing, EPRS, February 2024 (https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ BRIE/2024/757654/EPRS_BRI(2024)757654_EN.pdf).

6. Notably CTFs 150, 151 and 153. See: Combined Maritime Force (https:// combinedmaritimeforces.com/about/); EUNAVFOR Atalanta (https:// eunavfor.eu/) and EUNAVFOR Aspides (https://www.eeas.europa.eu/ eunavfor-aspides_en); ‘US announces naval coalition to defend Red Sea shipping from Houthi attacks’, The Guardian, 19 December 2023 (https:// www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/dec/19/us-announces-naval- coalition-to-defend-red-sea-shipping-from-houthi-attacks).

7. Ylönen, A., ‘On the Edge: the Ethiopia-Somaliland MoU’, ISPI Commentary, 30 January 2024 (https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/ on-the-edge-the-ethiopia-somaliland-mou-162032).

8. See: Chughtai, A. and Murphy, T., ‘Conflict and interests: Why Sudan’s external mediation is a barrier to peace’, ECFR Commentary, 8 September 2023 (https://ecfr.eu/article/conflict-and-interests-why-sudans- external-mediation-is-a-barrier-to-peace/).

9. SIPRI, Arms transfer database, values expressed as trend indicator values (TIVs)) (https://armstransfers.sipri.org/ArmsTransfer/TransferData).

10. ‘South Sudan mediation talks launched in Kenya with a hope of ending conflict’, Le Monde, 9 May 2024 (https://rb.gy/980eng); ‘Tagadum conference begins in Addis Ababa after one-day delay’, Sudan Tribune, 26 May 2024 (https://sudantribune.com/article286164/).

11. See: Horn of Africa Initiative (https://www.hoainitiative.org/); RFI, ‘New Red Sea alliance launched by Saudi Arabia, but excludes key players’,10 January 2020 (https://www.rfi.fr/en/africa/20200108-new-red-sea- alliance-formed-saudi-arabia-notable-exclusions).

12. See: Levy, I., ‘Emirati military support is making a difference in Somalia’, The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 18 March 2024 (https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/emirati-military- support-making-difference-somalia).