![]()

Russia is expanding its footprint in Africa. The First Ministerial Conference of the Russia–Africa Partnership Forum, held in November 2024, brought together foreign ministers from African countries and representatives of the African Union and regional organisations. Russian President Vladimir Putin pledged ‘total support’ for Africa, particularly in combating terrorism and extremism. Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova, quoted by RIA Novosti, said the conference dashed Western ‘dirty hopes’ for Russia’s isolation (1), underscoring Moscow’s strategic intent to deepen ties and bolster its influence in the region. These high-level engagements contrast sharply with the Western perception of Russia as a pariah, and reflect the growing support for Russia’s leadership across parts of Africa, particularly in West African countries like Mali and Burkina Faso. Gallup World Poll data shows that approval of Russia’s leadership increased by 22% between 2020 and 2023 across West Africa, despite Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine (2). But how widespread is this support, and how can it be explained?

This Brief seeks to address the lack of systematic, comparable data on Russia’s engagement in West Africa. Such data is crucial for assessing the threat posed by Russian-sponsored FIMI, which often serves as a tool to advance broader strategic objectives in regions where Russia seeks to expand its influence. Drawing on the legacy of Soviet military assistance during the Cold War and tapping into lingering anti-colonial sentiment, these FIMI campaigns spread disinformation and anti-Western narratives to influence public opinion and promote Russian interests.

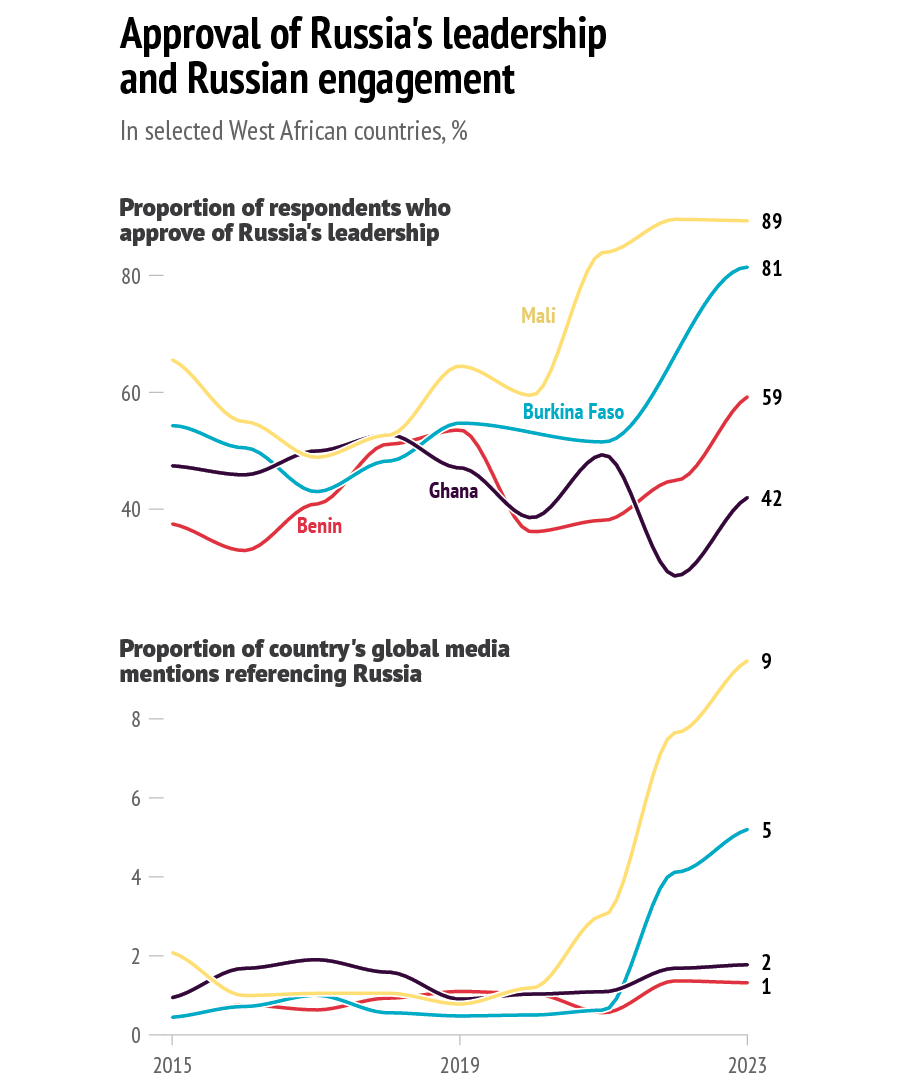

Data: Gallup World Poll data on approval of Russia’s leadership (N=1000 per country), 2024; Media-based proxy measure of Russian engagement, CFI Project, EUISS, 2024.

The Brief will examine trends in Russian engagement (using a media-based proxy measure capturing and quantifying any type of interaction between two countries), FIMI campaigns, and shifting public opinion. The analysis will focus on Mali and Burkina Faso – two countries experiencing the highest number of identified Russian FIMI campaigns and significant increases in public approval of Russia’s leadership (3). In line with the EU’s objective to counter FIMI in regions of strategic interest, an exploratory analysis will show how these trends have coincided, introducing a novel approach leveraging automated data extraction from online news sources (‘digital news scraping’) to construct systematic measures of foreign engagement. These can serve as a dynamic tool for EU policymakers to track patterns of Russian engagement and anticipate intensified FIMI campaigns, enabling more informed and timely strategic responses to this threat.

Russia’s expanding engagement in the Sahel

Russia’s engagement is particularly evident in Sahel countries like Mali and Burkina Faso, where the Wagner Group (now Africa Corps) has established a strong presence (4). Exploiting acute security challenges that governments and international partners have struggled to address, Wagner has positioned Russia as a viable alternative through swift, direct military support (5).

In fact, the presence and activities of Russia-linked paramilitary groups have emerged as tangible – yet shadowy and partial – indicators of Russia’s interests and engagement in African countries and across the world (6). Other signs of Russian involvement include formal trade or security agreements, or diplomatic summits. However, these indicators capture only a fraction of the broader picture and often rely on scarce data, particularly when it comes to smaller African countries.

A more dynamic and systematic approach is to examine engagement through media reporting, leveraging real-time digital news scraping to build proxy measures that go beyond any single dimension. Unlike narrow metrics, this approach quantifies diverse activities – such as trade and security deals, and diplomatic visits – all of which might otherwise remain overlooked. Critically, it provides consistent, high-frequency data even for smaller countries, enhancing the EU’s ability to track trends and anticipate the intensification of FIMI. One method involves using the Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone (GDELT), which monitors tens of thousands of news sources from nearly every country in over 100 languages. This extensive database reflects the volume of media coverage, not the validity of its content, and is used to measure how often a specific country appears in connection with Russia, providing a proxy for engagement. This measure captures the proportion of foreign (published outside the analysed country) media articles that mention, for instance, Mali, and that also reference Russia within a given timeframe. Frequent mentions of Russia alongside a specific country in global media suggest that Russia’s presence or actions are significant enough to warrant attention. Such visibility reflects tangible engagement, such as diplomatic efforts, military operations or economic investments, indicating Russia’s active role or impact in that country’s affairs. This provides a systematic and straightforward proxy measure of Russian engagement in Africa and beyond, offering a reference point for analysing its evolving impact.

Between 2020 and 2023, this media-based proxy measure of Russian engagement in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger surged by 703%, 940%, and 947%, respectively. In comparison, the same metric for Ghana and Benin saw more modest increases of 71% and 27%, respectively, over the same period. These engagement trends are in line with growing Western concerns about Russia’s expanding influence in Africa’s Sahel region, where a series of coups have coincided with shifting alliances and closer ties with Russia in countries such as Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger (7).

Focus on Mali and Burkina Faso

As part of this wider surge in Russian engagement, Russia has increasingly weaponised information through FIMI, including disinformation campaigns conducted ‘on an industrial scale’ (8). Indeed, West Africa, and particularly countries like Mali and Burkina Faso, has become a hotspot of information warfare. Two recent reports from the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, published in 2022 and 2024, highlight between them a fourfold increase in disinformation campaigns across Africa, with West Africa being the most targeted region, accounting for 40% of these campaigns, half of which are linked to Russia (9). For instance, while the 2022 report identified just one Russian disinformation campaign in Burkina Faso, this number had surged to eight by 2024 – the same count as in Mali for that year. The absolute numbers are relative and likely understated, given the opaque nature of such operations. Yet the significant increase in the number of disinformation campaigns identified by the same organisation – with similar capacity and resources – illustrates the growing scale and intensity of Russian information manipulation in West Africa.

In both Mali and Burkina Faso, diverse propaganda tools (e.g. Sputnik, African Initiative), extensive networks of coordinated inauthentic social media accounts, fake news sites, and AI-generated media content have been used to influence public opinion. These campaigns have sought to unite ‘pan-Africanists’, intimidate critics of the ruling juntas, and advocate for closer cooperation with Russia, while spreading anti-Western narratives and calling for an end to French military and diplomatic involvement. In Mali, these networks specifically called for a boycott of French media organisations Radio France Internationale (RFI) and France 24. These calls were seemingly heeded, as evidenced by subsequent changes in media accreditation and the banning of these French media outlets as of March 2022 (10).

This rise of Russian FIMI in West Africa is reflected in – and has likely contributed to – a significant increase in popular support for Russia’s leadership. Gallup survey data reveals that the proportion of respondents who approve of Russia’s leadership surged from 64% in 2019 to 89% in 2023 in Mali, and from 55% to 81% in Burkina Faso over the same period. In contrast, in Benin, approval ratings for Russia’s leadership saw a more modest increase, from 53% in 2019 to 59% in 2023. Meanwhile, approval of France’s leadership declined in both Mali and Burkina Faso – from around 50% to less than 20% – and fell slightly in Benin (from 63% to 58%). The graph on page 2 also shows the evolution of Russian engagement in these countries between 2015 and 2023, plotting the proportion of media mentions that involve Russia. For instance, in 2015, about 2% of media mentions of Mali included Russia; this increased to nearly 10% by 2023.

In West Africa, we observe a convergence between the level of Russian engagement and the rates of approval of Russia’s leadership, most strongly in Burkina Faso (with a correlation of 0.92) and Mali (0.87), meaning that as Russian engagement increases, so does the support for Russia’s leadership. Although data on FIMI campaigns is less reliable and comprehensive, there is a noticeable trend suggesting that the number of Russia-linked FIMI campaigns has expanded alongside the rise in both Russian engagement and support for Russia. However, this trend is not uniform across all contexts. For example, in South Africa, despite an increase in Russian engagement and FIMI campaigns between 2021 and 2023, public approval of Russia’s leadership has remained relatively stable at around 30%. In the context of West Africa, this trend appears most evident under certain conditions, including political instability, weak governance, and violent conflict – conditions that Moscow has been able to effectively exploit (11).

Boosting the EU’s early warning mechanism

West Africa is becoming a prime target in Russia’s hybrid warfare strategy. Exploiting instability and security vacuums, Russia’s growing influence in the region is a catalyst for conflict and undermines democratic aspirations while offering little in terms of development support (12). In countries such as Mali and Burkina Faso, the intensification of Russian FIMI campaigns, swaying public opinion in favour of Russia and against the West, is deeply concerning. The EU and its partners play a crucial role in supporting stability and growth in Africa through economic and development cooperation (13). To sustain their engagement in the region, the EU and its partners should actively counter Russian FIMI and anti-Western narratives, offering viable alternatives to Russian influence, which predominantly focuses on security rather than on promoting long-term development and stability (14).

Effectively countering Russian FIMI requires a proactive and data-driven approach. A key element of this strategy could involve systematically tracking Russian engagement across countries. The media-based measure of engagement outlined above could serve as a dynamic tool for EU policymakers to trace patterns of Russian engagement, as well as anticipate and mitigate intensified FIMI campaigns and potential shifts in public opinion. Notably, this measure flagged a sharp increase (a 1 576% rise between August and September 2021) in Russia’s engagement months before Wagner’s deployment in Mali, highlighting its potential as a robust monitoring and early warning system. Such tracking allows the EU to identify high-risk areas, tailor countermeasures such as strategic communication, and shape long-term policies by uncovering trends in Russia’s strategic priorities. While this Brief focuses on West Africa, these globally applicable tools can be utilised to inform counter-FIMI strategies in other regions, such as the Western Balkans.

Qualitative measures, using artificial intelligence (AI), may help assess the nature and characteristics of Russia’s engagement by analysing the retrieved news articles. The aim is to capture finer details, such as the cooperative or confrontational dynamics and the depth of Russia’s bilateral relationships, thereby offering a more nuanced understanding of its influence. Depending on the nature of the engagement and the context, a significant increase in Russian involvement can signal a broader strategic push, potentially leading to an escalation of FIMI efforts to consolidate influence.

By offering a global overview and a point of reference that complements on-the-ground intelligence, these metrics can help identify flashpoints and enable more informed and timely strategic responses to emerging FIMI threats. Beyond challenging and exposing Russian FIMI, the EU and its partners should proactively focus on rebuilding favourable public opinion by promoting positive narratives that highlight shared successes and that align with Africa’s aspirations for security and prosperity. This is an urgent task. Russia’s engagement and influence have rapidly intensified in recent years, particularly in countries like Mali and Burkina Faso, but also beyond. This has undermined trust in EU partnerships and destabilised long-term cooperation efforts.

References

1. Ross, W., ‘Putin offers African countries Russia’s “total support”’, BBC News, 10 November 2024.

2. Gallup World Poll Data, 2024.

3. Africa Center for Strategic Studies, ‘Mapping a surge of disinformation in Africa’, 2024; Gallup World Poll Data, 2024.

4. CNBC, ‘Russia’s Wagner Group expands into Africa’s Sahel with a new brand’, 12 February 2024.

5. Stronski, P., ‘Russia’s growing footprint in Africa’s Sahel region’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 28 February 2023.

6. Audinet, M. and Dreyfus, E., A Foreign Policy by Proxies? The two sides of Russia’s presence in Mali, IRSEM, Report 97, 2022.

7. Droin, M. and Dolbaia, T., ‘Russia: still progressing in Africa, but what’s the limit?’, Center for Strategic and International Studies, 15 August 2023; ‘Recent coups in West and Central Africa’, Reuters, 28 November 2023.

8. Peltier, E., Satariano, A. and Chutel, L., ‘How Putin became a hero on Africa TV’, New York Times, 13 April 2023.

9. ‘Mapping a surge of disinformation in Africa’, op.cit; Africa Center for Strategic Studies, ‘Mapping disinformation in Africa’, 2022.

10. Knight, T. and le Roux, J., ‘The disinformation landscape in West Africa and beyond’, Atlantic Council, 29 June 2023; ‘Mali to suspend French broadcasters France 24 and RFI’, Reuters, 17 March 2022.

11. Council on Foreign Relations, ‘Violent extremism in the Sahel’, 14 February 2024; Fund for Peace, ‘Fragile States Index’, 2024.

12. Ferragamo, M., ‘Russia’s growing footprint in Africa’, Council on Foreign Relations, 28 December 2023; Geröcs, T., ‘The transformation of African–Russian economic relations in the multipolar world-system’, Review of African Political Economy, Vol. 46, No. 160, 2019, pp. 317–335.

13. African Development Bank, ‘African Economic Outlook 2024’.

14. Africa Center for Strategic Studies, ‘Why Russia is on a charm offensive in Africa’, 26 July 2022; A Foreign Policy by Proxies? The two sides of Russia’s presence in Mali, op.cit.