You are here

Four swans of the Black Sea

Introduction

The Black Sea, nestled between the EU, Ukraine, Russia, Türkiye and the Caucasus, has become a major geopolitical hotspot. It is a key arena in Russia’s war on Ukraine, but also a contested space where broader geopolitical dynamics play out, with implications for maritime, energy, infrastructure and global food security. The EU has a strategic interest in investing in the security of the sea and the surrounding littoral. Its forthcoming Black Sea strategy (1) needs to be anchored in strategic foresight that anticipates various security scenarios for the region

Setting the scene

The course of Russia’s war on Ukraine as well as the evolving interplay between littoral states and key external actors including NATO (which now considers the region to be strategically important) (2), the United States and China will shape the security dynamics of the Black Sea in the mid-term perspective.

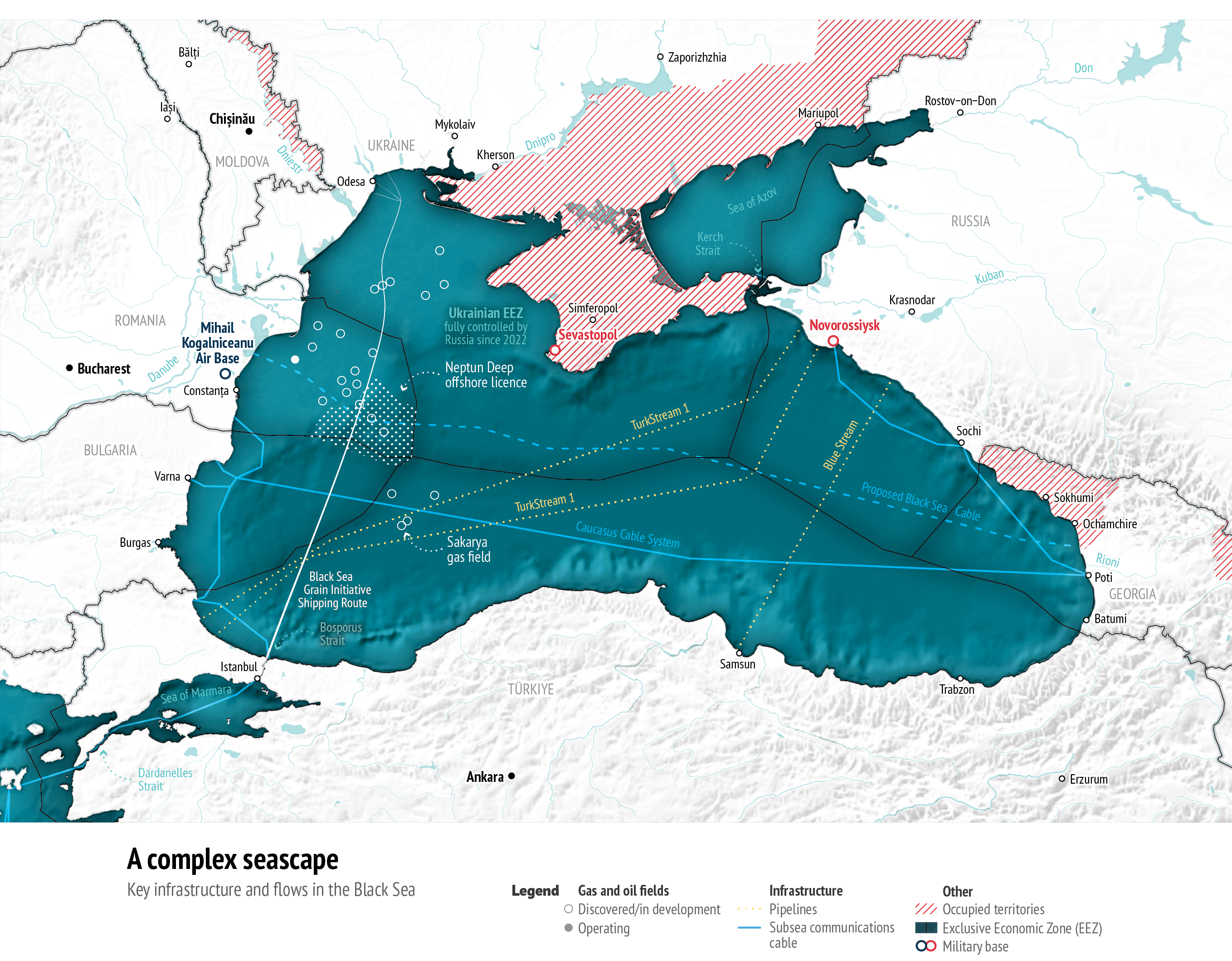

Data: Natural Earth, 2024; European Commission, GISCO, 2024; Global Energy Monitor, 2024; Flanders Marine Institute, ‘Marine Regions’, 2024

Russia is poised to remain a key driver of regional instability and insecurity. Its Black Sea fleet and its port and communication facilities have suffered severe damage due to Ukraine’s successful campaign using sea drones and missiles. As a result, one third of Russia’s vessels have been sunk or disabled (3), including the flagship Moskva, forcing the remaining ships to retreat to more distant ports (4). This has led Russia to relinquish control of the Black Sea’s northwestern sector, allowing Ukraine to resume exports from Odesa and operate safe sea lanes. Russia’s surface fleet has sought refuge in the better-protected Sea of Azov. Its capacity to replace its lost naval assets and to regain control while the Turkish Straits remain closed, hindering reinforcements from its other fleets, is in doubt. However, Russia retains its submarine force as well as its ability to launch long-range missiles including Zirkons and Kalibrs, from the sea.

Despite significant losses, it maintains maritime dominance. Furthermore, Moscow has turned Crimea into a strategic bastion and a potential springboard for projecting military power into Europe, the Mediterranean and the Middle East. Russia, with a long history of interference in the affairs of neighbouring littoral states - including stoking separatist movements, meddling in elections, exploiting economic dependencies as well as presenting a military threat to neighbours and restricting freedom of navigation – aspires to turn the Black Sea into a Russian lake. The future success or failure of this endeavour hinges on Ukraine’s defences, further disruption of Russia’s naval supply chains, the resilience of other littoral states and shoring up democracy in Georgia.

Four futures

Four potential security scenarios for the Black Sea region can be envisioned for the next decade: Lake Interregnum; Russian Lake; European Lake; and Lake Glacialis (or ‘Frozen Lake’).

- Lake Interregnum is a ‘standard projection’ representing the continuation of the current situation. In this scenario the Black Sea remains a a theatre of the unresolved confrontation between Russia and Ukraine, and by extension ‘the collective West’. Regional security mechanisms remain impotent, making all forms of security, including of maritime navigation and infrastructure, highly precarious and dependent on the current balance of power, with a constant risk of Russia’s ‘grey zone’ aggression.

- Russian Lake is a dystopian scenario. It envisions Russia’s aggressive advances on multiple fronts – through a successful offensive in southern Ukraine, skilful manipulation of domestic politics in Moldova and Georgia, and potentially pressuring Türkiye to reopen the Straits while at the same time deterring the entry of NATO’s forces. This would restore Russia’s naval power, and might lead to a shift in the current relationship between Türkiye and Russia. This scenario would essentially recreate a Cold War dynamic, with Russia controlling most of the Black Sea coastline as it did during the Soviet era, even if Romania and Bulgaria would now find themselves on the other side of the new ‘Iron Curtain’.

- European Lake, in contrast, is an optimistic scenario in which all littoral states except Russia are either EU Member States, close to accession or at least gravitating towards the EU. This could even include Türkiye – formally still a candidate state. Ukraine regains control of Crimea which ceases to be Russia’s strategic bastion. NATO and the EU manage to field denial and intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities to secure Black Sea navigation and critical infrastructure (including platforms and undersea cables). This unlocks the potential of regional cooperation, yielding gains from increased prosperity and connectivity.

- Finally, Lake Glacialis depicts a potential stalemate scenario. It would follow an escalation to a regional war into which NATO would inevitably be drawn. This outcome would resemble a new Cold War standoff, fracturing the region politically. However, a new form of pragmatic security management might emerge – perhaps as part of a broader reconstituted European security architecture. The specific form that this might take would depend on the outcome of the war and could range from measures to prevent escalation to arms control and even demilitarisation. While the likelihood of a regional war should not be overestimated, given the Kremlin’s revisionist ambitions and the militarisation of the Black Sea region it is a possibility that should not be ruled out.

The many shades of Russian aggression

Of the scenarios outlined above, it is ironically the first, the ‘standard projection’, that appears to be the one least likely to materialise by 2030. Russia’s use of aggressive tactics, both military and non-military, in its effort to change the status quo, combined with the lack of effective security measures, make the current situation highly unstable. The EU’s future actions will be crucial in steering the region’s trajectory in the direction of one of the other scenarios. These actions will comprise responses to foreseeable incidents with security implications for the EU and its Member States.

Russia will invariably be the instigator of these incidents, which will unfold against a continuous barrage of disinformation campaigns, electoral interference and low-scale cyberattacks. The only exception might be incidents caused by floating sea mines posing risks to all parties’ vessels and oil and gas exploration platforms. But even these silent threats will be legacies of Russia’s current war of aggression.

The most serious risk lies in Russia employing limited aggression. This strategy would ‘up the ante’ of contestation in this key European security theatre with the intent to divide and weaken Member States seeking to respond to Moscow’s revisionist geopolitical ambitions. Combined with foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI), such aggression could target various undersea infrastructures – pipelines, submarine cables, drilling platforms – as well as vessels and sea lanes. The tactics could range from cyberattacks and kinetic strikes (drones, missiles, planting mines), to the seizure and occupation of manned facilities such as drilling platforms, possibly by covert military forces. Beyond the material damage caused by such subversive activities in the maritime domain, the symbolic dimension of Western infrastructure being attacked should not be underestimated. For example, a new EU-funded data and electricity cable traversing the Black Sea from Georgia to Romania could be targeted once constructed. Russia’s seizure of Ukrainian platforms following the annexation of Crimea (5) sets a dangerous precedent for other littoral states currently engaged in a number of offshore gas extraction activities, notably Romania’s Neptun Deep or Türkiye’s Sakarya project. Recent events underscore this threat. Russia has not only seized control of Ukraine’s EEZ; in September 2023, it also temporarily blocked Bulgaria’s access to theirs. The previous month, Russia intercepted and boarded Türkiye’s Şükrü Okan cargo ship within this same zone. While Russia’s withdrawal of its surface fleet – resulting also in the lifting of Ukraine’s trade blockade – reduces the immediate risk of similar incidents, Moscow can still use its submarines to mine key shipping lanes in the western Black Sea.

These actions represent potential tools in Russia’s hybrid warfare arsenal, scalable and combining both kinetic and non-kinetic capabilities to test the EU’s response. Robust contingency planning is crucial to prevent the EU being caught offguard and responding erratically, oscillating between overreaction and underreaction, which Russia could further exploit to its advantage. The risk of insufficient preparedness is a drift towards the Russian Lake scenario – or, if a crisis stirred by the Kremlin were mismanaged by either party, an open regional war and subsequent Lake Glacialis. The latter risk exists also for mishandled security incidents such as encounters between Russian and US aircraft (6), as Moscow’s objections to US reconnaissance flights over the Black Sea aiding Ukrainian forces is a likely source of future friction. Whatever the trigger, a regional war could entail a potential of horizontal escalation beyond the Black Sea region. There would also be a possibility, however remote, of vertical escalation, with Russia resorting to the use of nuclear weapons to ‘de-escalate’ and deter more substantial intervention by NATO in defence of its members.

Chance favours the prepared

The EU’s ongoing support for Ukraine’s defences is essential for preventing the dystopian Russian Lake scenario from materialising. Russian occupation of Ukraine’s Black Sea littoral would significantly weaken regional security for other states. Therefore it is imperative to deny Russia control of the coastline and to bolster Ukraine’s ability to challenge Russian naval assets and more efficiently disrupt its sea supply lines. EU Member States should moreover strengthen deterrence of Russian aggression by building up their naval and missile defence capabilities. Ukraine’s innovative use of sea drones, with fleets individually performing specialised tasks traditionally requiring expensive modern vessels, could serve as a source of inspiration here even for smaller militaries.

This military reinforcement should be integrated into a more comprehensive security strategy focused also on deterring and defending against Russia’s use of subversive grey zone tactics. Reinforcing security in the Black Sea requires enhanced situational awareness and early action capabilities, which can be achieved through streamlining the use of existing assets including CSDP missions. Further efforts should focus on building resilience against hybrid threats by developing new joint response mechanisms. They should also entail a focus on critical maritime infrastructure. The EU should revisit options for a new CSDP operation or even a Coordinated Maritime Presence (CMP). It should also explore ways to engage with NATO’s maritime security centre of excellence, potentially making it a joint initiative, and consider contributing to the demining mission building on the currently operating Mine Countermeasures Black Sea Task Group launched by Romania, Bulgaria and Türkiye. The mission tackles the immediate threat of drifting sea mines but it could also serve as a foundation for future multistakeholder security cooperation, building on the experience of an emerging security ‘community of practice’ (7).

By taking these steps, the EU would demonstrate its commitment to achieving its broader maritime security objectives as enshrined in the EU Maritime Security Strategy (8). In the final instance, however, the most potent tool that the EU has at its disposal to turn the Black Sea into a safe and prosperous ‘European lake’ is its own gradual enlargement.

References

*The author would like to thank Pelle Smits and Smaranda Olariu for their invaluable research assistance, as well as all participants at the internal roundtable convened by the EUISS for sharing their inspiring views on the subject.

1. The European Council invited the Commission and the HR/VP to prepare a joint communication on building a strategic approach to the Black Sea in its Conclusions from 27 June 2024 (https://www.consilium.europa.eu/ media/qa3lblga/euco-conclusions-27062024-en.pdf).

2. ‘NATO 2022 Strategic Concept’, 29 June 2022 (https://www.nato.int/ nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/2022/6/pdf/290622-strategic-concept. pdf); NATO, ‘Vilnius Summit communiqué’, 11 July 2023 (https://www. nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_217320.htm); NATO, ‘Washington Summit communiqué’, 10 July 2024 (https://www.nato.int/cps/en/ natohq/official_texts_227678.html).

3. Boyse, M., Scutaru, G., Colobasanu, A. and Samus, M., ‘The battle for the Black Sea is not over,’ Hudson Institute, April 2024 (https://www. hudson.org/security-alliances/battle-black-sea-not-over-matthew- boyse-george-scutaru-mykhailo-samus-antonia-colibasanu).

4. Yet Ukraine has demonstrated the capacity to hit even these facilities, notably the port of Novorossysk. Russia’s plans to build a new military port in Ochamchire in the occupied breakaway region of Abkhazia should be seen in this context.

5. Two floating platforms known as Boyko Towers as well as two rigs, Tavrida and Syvash, used by Russia for military purposes following their occupation, were subsequently reclaimed by Ukraine in 2023.

6. An MQ-9 Reaper drone was destroyed after having been damaged by a Russian Su-27 over the Black Sea in March 2023.

7. It is worth remembering here the part the WEU’s initial operational experience through the mine-clearing operation Cleansweep in the Strait of Hormuz (1987) played in the progressive building up of the European defence pillar and eventually the CSDP.

8. European Commission, ‘An enhanced EU Maritime security strategy for evolving maritime threats’, JOIN(2023) 8 final, 10 March 2023 (https:// oceans-and-fisheries.ec.europa.eu/document/download/7274a9ab- ad29-4dae-83fb-c849d1ca188b_en?filename=join-2023-8_en.pdf).